B. A. Hussainmiya

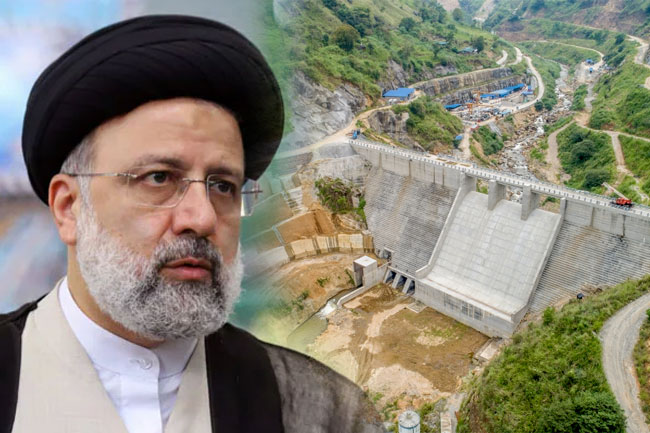

COLOMBO: The vesting of the Uma Oya project, jointly officiated by Iranian President Ibrahim Raisi and President Ranil Wickremesinghe, marks a key event in the Sri Lanka-Iran collaboration. Through the Uma Oya multipurpose project, Iranian businesses in Sri Lanka initiated the most important technical and engineering service projects to increase the irrigation of 5000 acres of agricultural land, transferring 145 million cubic meters of water besides generating 290 GW/h of power annually.

This post tries to celebrate this milestone by emphasising some essential features of historical links between our two nations. To begin with, diplomatic relations between Iran (then known as Pahlavi Iran) and Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon) started in 1961 via the Ceylonese embassy in Islamabad, which was the closest Ceylon had to a presence on Iranian soil until the opening of the Tehran embassy office in 1990. Tehran set up its Colombo office in 1975.

Persia, now Iran, has been an illustrious nation with high historical and cultural achievements. It is home to one of the world’s oldest continuous major civilizations, with historical and urban settlements dating back to 4000 BC. Friedrich Hegel calls the Persians the “first Historical People”. The country’s first great city, Susa, was built on the central plateau around 3200 B.C. In 559 B.C., the Persian Empire arose in southwestern Iran and conquered the Mesopotamians and Egyptians. Once a major empire, Iran has endured invasions by the Macedonians, Arabs, Turks, Mongols and others. Iran has continually reasserted its national identity throughout the centuries and has developed as a distinct political and cultural entity.

The Muslim conquest of Persia (633–654) ended the Sasanian Empire and was a turning point in Iranian history. Islamization of Iran took place during the eighth to tenth centuries, leading to the eventual decline of Zoroastrianism in Iran as well as many of its dependencies. However, the achievements of the previous Persian civilizations were not lost; they were, to a great extent, absorbed by the new Islamic polity and society.

Historically, relations between Iran and Sri Lanka date back to the pre-Christian era. Sri Lanka lies almost midway between the Horn of Africa and the Straits of Malaya. Its importance should have been tremendous in the past to mariners and merchants as a necessary stop-over and entrepot. Its significance then should have been felt in the absence of steam power and improved navigational technique, equipment and telecommunication. Phoenicians, Sabeans, Greeks, Romans, Persians, Arabs and Malays crisscrossed the island of Ceylon and left their traces in trade and cultural exchanges.

Cosmas Indicopleustes, the Greek writer of the sixth century testifies to the existence of amicable relations between the two countries and also attested by a number of other foreign writers of this period. Cosmas stated in his “Topographia Christiana,” that the ports of the island of Sri Lanka were much frequented by ships from all parts of India, Persia, and Ethiopia. Procopius informs that the Romans obtained their Chinese silks from the Persian traders who had brought those items from Sri Lanka. The Indian Buddhist monk Vajrabodhi (seventh century) had seen a fleet of thirty five Persian ships at the ports of Sri Lanka whilst he was travelling from India to Sumatra in one of those ships. A Chinese text named Hwi-chao written around 729 A. D. also attests to the brisk commercial activity between Sri Lanka and Persia.

The Iranian Sea-faring merchants formed the nuclei of Christian settlements about 550 AD. The Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Faxian in the early 5th century testified the presence of East Iranian or Sogdian merchants in Ceylon. Due to the long distance between Persia and Ceylon, these merchants began to settle down on the island. There were enough Christians from Persia to form a local pastoral community in the capital. From the unearthed ‘Nestorian’ cross and the land of origin of these Christians, which early travellers described, one can be sure that these Persian Christians belonged to the Church of the East (‘Nestorian’) or East Syriac Church.

Thus in the century before Islam’s rise, the Persians reigned supreme in commercial activities in the Indian Ocean. Their merchants were firmly rooted in the entrepôt trade frequenting harbours of India and Sri Lanka (Mantai). They traded with China and the Far Eastern countries even earlier than the Arabs. By this time, Sri Lanka obtained a firm position in the international commerce and trading system. Although not a commercial production centre, Sri Lanka became a supply and distribution centre of commodities and a main naval centre in the Indian Ocean; as such, Sri Lanka became a reputed maritime base with a well-organized shipping system in the region. With its numerous bays and anchorages for ships, the island served in ancient and medieval times as a centre of transit trade. Being rich in gems, pearls, ivory, cinnamon, etc., Ceylon attracted foreign merchants such as Persians, Arabs and Indians. Meanwhile, Ceylon imported horses from Persia. The most attractive goods from Ceylon were pearls and precious stones, which could be refined for jewellery by artisans back in the Middle East – a traditional profession of many Syriac Christians. According to historian G. W. Wolters, the Chinese sources as early as A.D. 380 refer to a Persian king who asked for the hand of the daughter of a king of Sri Lanka and sent a gold bracelet as a present. Trade must have been very profitable and prosperous for these Persian Christian merchants since they already possessed beautiful houses in a residential area in Anuradhapura.

It must be noted that Silver Lariat of Fish Hooks coins of Persia and Gold Seraphins of Ormus have been used in those days for mode of currency which were mostly available in Persian Gulf area. It was revealed that, as Sri Lankans have potential to find Pearl, Gem, Iranian had deployed many Sri Lankans for Pearl fishing in Gulf area. Historian Ibn Miskawaith (d.1029 A.C) had revealed that many delegations of King of Sri Lanka had visited Persia with precious Gifts, Pieces of Teakwood composed with Pearl, Elephants etc. but it was difficult to trace the years of visits. Later on Iranian emperor had sent an Army to Sri Lanka after a battle had subdued, had taken our valuable Pearl, Ruby Gem, Precious Stones, Herbs, Spices etc and reference are made in this regard by Al-Istakhi (d. 951 A.C) and Al Beruni (d. after 1058 A.C). Al-Beruni (A.D.1048) also refers to a dispatch of a diplomatic mission along with ten elephants, two hundred thousand pieces of teakwood, and seven divers (of pearls) sent by Sarandib to Khusraw Nushirvan mentioned in Kitāb al Jamāhir fi Marifat al Javahir as cited by S. A. Imam.

There were many clues that some Physicians of Sarandib (Ceylon) had been utilized for treatments. Among the materials in recent excavations attributed to Persian origin was a Partho-Sassanian pitcher from Jetavanarama from the citadel in Anuradhapura. Besides large quantities of Sassanian-Islamic ceramics and a baked clay bulla with three impressions of the The Sassanian period was found in Mantai. According to Bopearachchi, when defining the design of the interior city, the royal pleasure gardens and the palace, the ancient site of Sigiriya, were, to a certain extent, influenced by Persian architecture.

Around the middle of the 7th century A.D., Persia, which had been exhausted by the uninterrupted wars for supremacy with Eastern Rome – the Byzantine Empire and the Abyssinian ally of Byzantium, However, by adopting Islam, Iranian imperial power strengthened its ascendancy. Furthermore Iran adopted the Arab script which replaced the old Pahlevi script. A significant change took place when Arab-Sri Lankan contacts as Arab commercial activity gained a fresh impetus in her association with Islamised Persia and the Persians North Indians and their ubiquitous compatriots, the Negroes of the East African coast. In the 9th and 10th centuries, it was this conglomerate of the Persians, the Arabs and the Abyssinians, all Islamised and speaking the Arab tongue, hence for the sake of convenience, designated “Arab” which dominated the Indian region.

Iranian influence in Sri Lanka did not disappear with the progress of the Arabization process. Most Muslims in Sri Lanka are Sunnis. There are Shia Muslims too, say from from the relatively small trading community of Bohras. The division between the Shias and the Sunnis dates back to the death of Prophet Muhammad and stems from a question over who was to take over the leadership of the Muslim nation. There is much evidence of continuous Iranian Shia influence in Sri Lanka among the Moors and Malays, who were Sunni Muslims and followers of the school of Imam Shafi. The veneration of Imam Ali and Fathima, the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad (Sal), continues in the eulogia literature and spreads far and wide on the island. Indian military arrivals of Shia persuasion during the British times strengthened several Iranian practices, such as celebrating the Muharram events of the Pancha ceremony and the like. Moreover, Malay literary texts discovered in Sri Lanka not so long ago contain considerable literary genres referring to the marriage of Ali to Fathima and other epic texts translated from Persian into Malay and Arabu-Tamil and so on.

The literary connection between Iranian and local literature is a big topic that future scholars on Islam need to investigate and elaborate on. ( The writer Dr. Haji B. A. Hussainmiya Ph.D is a historian who has now retired from Teaching after 45 years at Universities of Peradeniya and Brunei.)